Ultra-processed foods have a way of slipping into the busiest corners of life. They show up when you are rushing out the door, when you are eating with one hand while answering messages, and when you are tired enough that the idea of chopping an onion feels like a personal insult. They promise comfort without asking for much in return. You open a packet, twist a lid, tear a seal, and pleasure arrives instantly. When people describe these foods as “addictive,” they are usually describing that quiet, persistent pull: you were not truly hungry, yet you want it; you finished what you planned to eat, yet you keep thinking about more; you feel a momentary lift, then you are looking for the next lift again. That pull is not a character flaw, and it is not simply about willpower. It is what happens when modern food design meets an ancient reward system. The human brain is built to learn quickly from rewards because, for most of human history, energy-dense food was not guaranteed. When a certain taste signaled calories, survival improved. The brain became excellent at noticing patterns, remembering where reward came from, and nudging you toward it again. Ultra-processed foods give that system something unusually powerful: a reward that is consistent, intense, fast, and easy to repeat.

Consistency matters more than people realize. When a food tastes almost exactly the same every time, the brain learns to trust it. The sweetness is predictable. The salt hits at the same moment. The crunch lands the same way. There is no uncertainty, no awkward bite, no seasonal variation. You do not have to work for the pleasure and you do not have to wait for it. In learning terms, this is a perfect setup. Reliable reward strengthens habit loops. Over time, cues begin to do the work that hunger once did. A specific brand color, the sound of a can opening, the sight of a familiar bag in the pantry, the time of day you usually snack, even a certain mood can trigger craving before you have made a conscious choice. In that moment, it can feel as if your body is craving the food itself, but often it is craving the learned promise of relief and pleasure.

Ultra-processed foods are also built to hit what food scientists sometimes call a “sweet spot” of palatability. Many whole foods have natural limits. A banana is delicious, but it becomes overly sweet after a while. A rich stew is satisfying, but at some point you feel finished. Even favorite foods often contain a built-in stopping point, a sensory moment when “enough” becomes obvious. Many ultra-processed foods are designed to delay that moment. Their flavors are tuned to stay exciting, to keep the mouth interested, to avoid tipping into “too salty” or “too sweet” too quickly. This is not a conspiracy in the dramatic sense. It is a design goal in competitive markets where repeat purchase matters. If a snack is pleasant but easy to stop eating, it may not sell as well as a snack that quietly invites one more bite, then another.

One reason this invitation is so effective is the way ultra-processed foods combine ingredients that rarely appear together in nature at such high intensity. Sugar, fat, and salt each signal something meaningful to the brain. Sweetness hints at quick energy. Fat suggests density and satisfaction. Salt sharpens flavor and can make foods feel more vivid. When these signals stack in one bite, the reward can feel larger than the sum of its parts. The brain lights up because it has encountered a compact, concentrated experience of energy and pleasure. Even if you know, rationally, that you have already eaten enough, the sensory message remains persuasive: this is valuable, keep going.

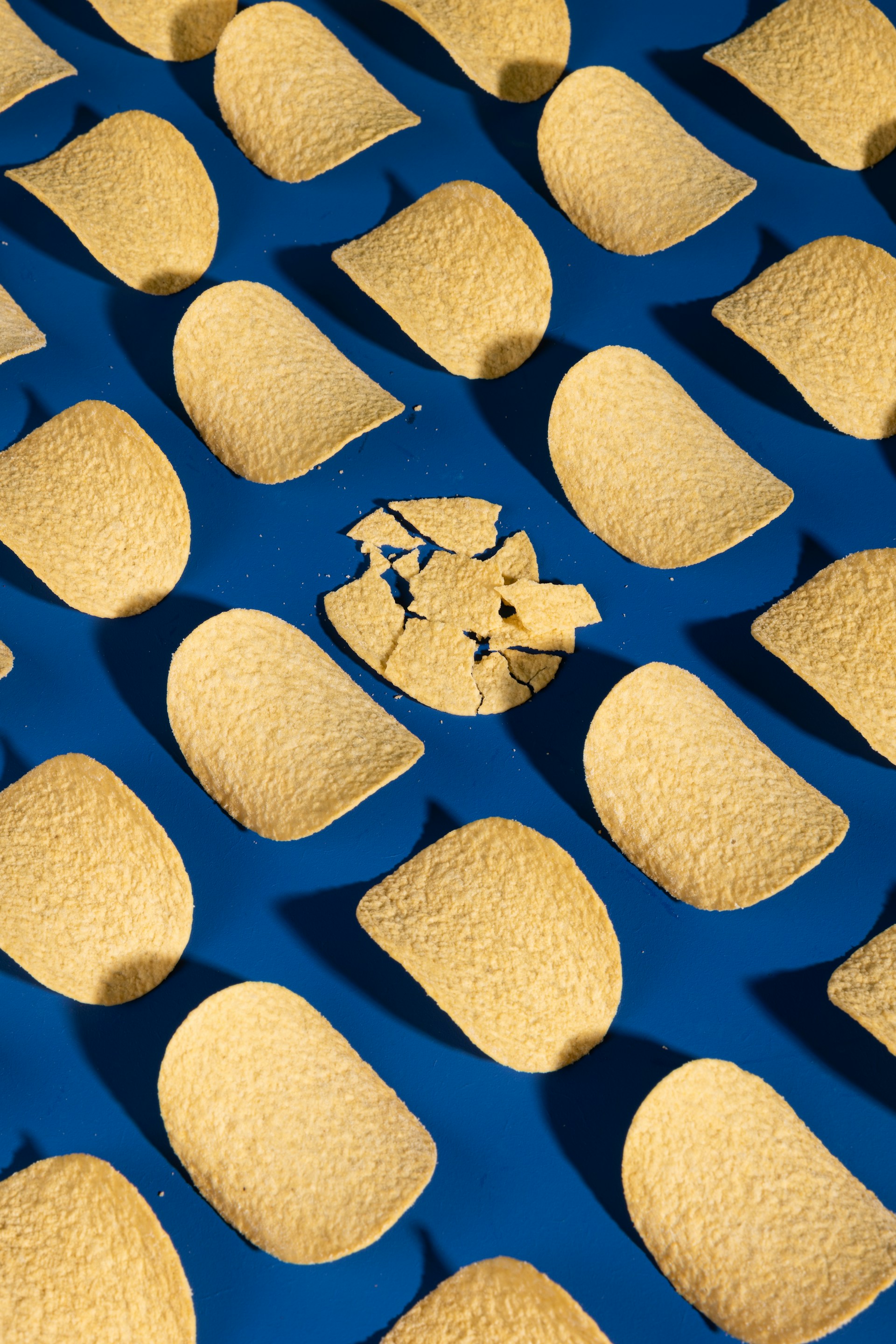

Texture deepens the effect in ways most people overlook. Eating is not just taste. It is also sound, mouthfeel, and effort. Many ultra-processed foods are engineered to reduce effort and increase speed. Think of airy chips that melt quickly, cookies that dissolve as they warm, chocolates that seem to disappear the moment they hit your tongue. When food requires less chewing and slides down easily, you can eat more before your body catches up. Fullness signals do not arrive instantly. Your stomach needs time to stretch, your gut needs time to process nutrients, and hormones involved in satiety need time to rise and deliver their message. If a food can be eaten rapidly, it can outrun those signals. You may consume far more than you intended before the feeling of “I am full” finally lands. At the same time, certain textures are simply memorable. Crunch, snap, fizz, creamy melt, and sticky chew create a distinctive sensory signature. Distinctive experiences are easier for the brain to store and recall. Later, when you are stressed or bored or simply walking past a shop, your brain can replay that signature and create a craving that feels strangely specific. You are not just craving “food.” You are craving a sensation.

Another part of the puzzle is that many ultra-processed foods are less effective at triggering the body’s deeper signals of satisfaction. Satiety is layered. It includes the physical sensation of fullness, but also the quieter sense that your body has received what it needs. Protein and fiber play a major role here. Protein tends to produce lasting fullness because it influences appetite hormones and provides building blocks the body values. Fiber slows digestion, supports steady energy, and feeds gut bacteria that can influence satiety signals over time. Many ultra-processed foods are calorie-dense while being relatively low in protein and fiber. The result can feel like a strange mismatch: you have consumed a lot of energy, yet you do not feel truly settled. This mismatch is one reason people can snack and snack and still feel unsatisfied. The food delivers quick pleasure and quick calories, but it does not provide the structure your body uses to register “enough.” In some people, refined carbohydrates and added sugars can also contribute to faster rises and dips in blood glucose, which can intensify cravings later in the day. The details vary from person to person, but the lived experience is familiar: you eat something sweet or starchy, you feel a brief lift, and then you feel a drop that makes you want another lift. When this pattern repeats, it becomes a loop.

Additives and flavor technologies can strengthen the loop further. Ultra-processed foods often contain flavorings, sweeteners, emulsifiers, and other ingredients that help products stay stable, look appealing, and taste consistent across time and geography. Research on how specific additives influence appetite regulation and the gut is still developing and not always straightforward. What is clearer is that louder, more persistent flavor makes continuing to eat easier. When a food stays intensely interesting, each bite feels rewarding enough to justify the next one. If the flavor is powerful without being paired with lasting fullness, the desire to keep eating can remain surprisingly strong.

Modern life adds the final, very human layer. Ultra-processed foods thrive in the same conditions that make many people feel stretched: stress, fatigue, lack of time, and irregular routines. When you are stressed, your brain prioritizes quick relief. When you are sleep-deprived, appetite regulation can shift in ways that increase hunger and cravings, especially for high-reward foods. When your days are fragmented, you may not have consistent meals that anchor your energy, so snacking becomes the default structure. In that environment, ultra-processed foods are not merely available. They are perfectly suited to your nervous system’s needs in that moment. They require no planning, no cleanup, no pause. They fit into a commute, a late-night scroll, and the emotional exhaustion that follows a long day.

Marketing and packaging also shape the experience in ways that can feel invisible until you notice them. Many ultra-processed foods are framed as treats, rewards, comfort, fun, and identity. They are associated with celebration and relief. They are designed to catch you at checkout counters and petrol stations because decision fatigue makes impulse more likely. Even the language on packages can be persuasive. “Single-serve” often contains more than one true serving. “Resealable” suggests you will stop, but the product inside may be designed for continuation. Portion sizes can quietly expand what feels normal. When you repeatedly pair a food with comfort and convenience, the craving becomes layered. You are not only craving the taste. You are craving the feeling of being taken care of with minimal effort.

There is also the issue of sensory contrast. Many whole foods are gentle. Plain rice, oats, vegetables, simple soups, and lightly seasoned proteins are not meant to shout. They are meant to nourish and satisfy. But once your palate becomes used to highly amplified flavors, ordinary foods can start to feel dull by comparison. This is not because the foods have lost value. It is because your baseline has shifted. The brain adapts quickly to intensity. If your everyday eating pattern includes many high-contrast foods, your tongue and brain can begin to expect louder signals, and quieter signals can feel unsatisfying. The craving for ultra-processed foods can then look like a craving for excitement, because in a sensory sense, that is what it is.

The encouraging part is that baselines can shift back. Taste is not fixed. It recalibrates with repeated exposure. This is why harsh, all-or-nothing rules often backfire. When people try to remove every ultra-processed food overnight, they may feel deprived, especially during stressful weeks. Deprivation can make the brain cling harder to the idea of reward. A gentler approach tends to work better because it respects the realities of modern life while still loosening the loop.

A gentle reset often begins with rhythm rather than restriction. When meals become more predictable, the nervous system relaxes. When you eat enough earlier in the day, cravings later often soften. When you build meals that include protein and fiber in a satisfying way, your body receives a steadier signal of “I am safe and fed.” This can look like simple, comforting combinations rather than perfect ones: yogurt with fruit and seeds, eggs with a warm carb and vegetables, a soup with legumes, a rice bowl with tofu or fish and something crisp on top. The goal is not purity. The goal is stability. It also helps to create what I think of as bridge foods, options that live between ideal and real. Many people reach for ultra-processed foods because they are fast. So the practical answer is not simply “do not eat them.” The practical answer is “what is the easiest thing that still steadies you.” A banana with peanut butter, crackers with cheese, a simple sandwich, leftovers you actually like, instant noodles upgraded with an egg and vegetables. These options reduce the spike-and-crash pattern while still respecting the need for convenience. When your body feels steadier, the craving loop often becomes less dramatic.

Your environment matters too. Foods you see first become foods you eat more often. If the first thing you see when you open the pantry is a bright bag, your brain receives a cue before you are even hungry. If you place more nourishing, satisfying options where your eyes land first, the cue changes. This is not a trick. It is an acknowledgement that humans are cue-driven creatures. You do not have to fight cues if you can design them. Most importantly, cravings are information, not evidence of failure. A craving often appears where your day is leaking energy. It may point to under-eating earlier, sleeping too little, feeling overwhelmed, or seeking a break you have not allowed yourself. Ultra-processed foods did not create those conditions, but they offer quick relief within them, and the brain learns that relief fast. When you respond to cravings with curiosity rather than shame, you can start to see what your body is actually asking for. Sometimes it is food. Sometimes it is rest. Sometimes it is steadier meals. Sometimes it is simply a pause.

In the end, ultra-processed foods can feel addictive because they are designed to be reliably rewarding, easy to consume quickly, and less likely to trigger lasting satiety. They also fit modern life so well that repetition becomes effortless. But the deeper story is not that people are weak. It is that these foods align perfectly with a tired nervous system and a crowded schedule. When you build rhythms that support steadier eating and a calmer pace around food, the spell often weakens. Not overnight, and not through harsh rules, but through repeated moments of feeling genuinely satisfied. Over time, you may find that cravings become quieter, simpler foods become more appealing again, and eating feels less like a tug-of-war and more like care.