In many group chats and comment sections, the word “chopped” appears as if it is harmless slang. It is usually delivered with a laugh, a string of emojis, or a casual tone that suggests no serious harm is intended. Yet for the person on the receiving end, being labelled “chopped” can feel less like a joke and more like a verdict on their value. Over time, that label can deeply affect how they see themselves, how they move through friendships, and how stable their mental health feels.

When someone is called “chopped”, the message is often that they are undesirable, irrelevant, or not worth considering. It might start as a reference to looks or style, but it rarely stays in that narrow lane. Human beings are wired to scan constantly for signals about where they stand in a group. The brain treats labels as data points that reveal whether there is belonging, respect, and safety. Even when a word like “chopped” is dismissed on the surface as “just banter”, the nervous system hears something more serious. It registers a potential drop in status or acceptance, and that can quietly activate stress.

The first time a person hears this label from friends, they might brush it off, laugh along, or reply with a sarcastic comeback. The mind tries to protect itself by minimising the moment. However, if the label keeps showing up, especially in the same group or from the same people, a shift begins to happen beneath the surface. The brain starts to categorise the insult as evidence. It becomes less about “they said this once” and more about “this is how they see me”. After a while, the mind generalises from one context to many others. A comment about how someone looks in one photo becomes a sweeping statement about their appearance all the time. A supposedly playful insult in one situation is treated as a summary of their entire personality.

Eventually the label becomes internalised. The story changes from “they called me chopped” to “I am chopped”. At that point the word stops being an external description and starts to feel like an internal identity. When that happens, mental health is no longer dealing with a single rude comment. It is dealing with a deep belief about self worth.

Self esteem rarely collapses in one dramatic moment. It is more like a slow drip. Each “joke” that positions someone as the unattractive one, the leftover one, or the one nobody would choose can chip away at core beliefs. A person may start doubting whether they are worthy of attention in social spaces. Instead of sharing ideas freely or taking up normal space in conversations, they might shrink themselves. They speak less, they allow interruptions, and they start expecting that others will overlook them. The standard for how they should be treated sinks quietly lower.

At the same time, their belief in their own value and contribution can begin to fade. If they are always the punchline or the one slightly outside the circle, they may hesitate before sharing an opinion or volunteering for anything that makes them visible. Silence feels safer than risking another humiliating moment. Over time, this avoidance can create a sense of invisibility. The person may start to feel that they are fundamentally “less than” everyone else, not because of objective facts, but because a repeated label has shaped their narrative.

There is also the question of whether change feels possible. When a label like “chopped” feels fixed, effort can start to seem pointless. Instead of thinking “I am still finding my style” or “I am still building confidence”, the internal voice jumps straight to “I am just chopped and nothing will change that”. This kind of thinking is heavy. It removes hope and weakens motivation, which are both important anchors for mental health. It is not surprising that persistent self criticism is linked with higher risks of anxiety and depression. The effects of being labelled chopped on mental health often start precisely here, in the quiet shift of what someone believes they deserve.

Once a label has sunk in, the brain also begins to scan the environment for confirmation. This is a normal function of pattern detection. After being called “chopped”, a person might find themselves replaying photos to check how they look compared to others. They might over analyse every reaction whenever they send a selfie or update their profile picture. Posting online can become a stressful act rather than a simple form of expression. Notifications, which used to be neutral or fun, become small spikes of anxiety. There is an expectation that another joke or cutting comment might be waiting.

This constant scanning can evolve into social anxiety. The body may react with a faster heart rate, tense muscles, or unsettled sleep before social events. Even mundane interactions can feel loaded, because each one carries the potential for a repeat of the label. Hypervigilance like this consumes a lot of mental energy. When part of the mind is constantly preoccupied with monitoring how others are perceiving you, there is less capacity available for focus at work, in class, or in creative projects. The person may end the day feeling exhausted without fully understanding that much of the tiredness comes from managing a sense of ongoing social threat.

Not everyone responds to being labelled “chopped” by withdrawing. Some people move in the opposite direction and begin to overcompensate. They might pour extra effort into the friendship group in hopes of securing their place. They become the one who plans meetups, remembers important dates, or listens to everyone else’s problems. They accept cruel jokes because they fear that speaking up will make them “difficult” or replaceable. This is a form of people pleasing that does not come from generosity but from fear. The unspoken logic is “If I am useful enough and easy enough, they will keep me around”.

This pattern can have long term consequences. It trains someone to accept poor treatment and one sided effort as normal. Boundaries blur. Emotional labour is given freely, yet respect is not consistently returned. Standards quietly shift for what friendship should feel like. In the future, this person may tolerate similar dynamics in romantic relationships or workplaces, because the template for “what I get” was set earlier by friend groups that did not treat them with consistent dignity.

The impact of this kind of labelling extends into performance and risk taking. When someone starts to believe that they are unattractive, uninteresting, or fundamentally “not it”, they may stop stepping into spaces where they could thrive. They turn down opportunities that would place them in the spotlight. They avoid trying new activities where they think they will be judged on appearance or skill, such as joining a sports team, taking a dance class, or presenting in public. The fear of being perceived through the “chopped” lens suppresses healthy experimentation and growth.

On the other end of the spectrum, some people respond by pushing themselves intensely. They might jump into extreme diets, punishing exercise routines, or overwork in school and career, not from a place of wanting to grow, but from desperation to escape the label. This urgency can generate short bursts of change, but it is rarely sustainable. Living with constant self pressure elevates stress hormones, disrupts sleep, and increases the risk of burnout. A system built on fear rather than self respect is unstable. Eventually, the body and mind push back through fatigue, irritability, or loss of motivation.

The source of the label also matters. Insults from random strangers certainly hurt, but when “chopped” comes from friends, the injury goes deeper. Friend groups often normalise their language and make it sound like everyone is fine with it. If a person raises discomfort and is told they are “too sensitive” or that they “cannot take a joke”, it adds another layer of confusion. They begin to doubt their own emotional signals. They start thinking that perhaps they are the problem rather than recognising that the dynamic itself is unkind.

This self doubt can create a kind of internal disconnection. When someone repeatedly tells themselves that their feelings are invalid, they may lose touch with the inner sense that usually warns them when something feels off. That makes it harder to set boundaries in future situations because the internal alarm system has been trained to stay quiet. Alongside this, there may be grief. Realising that people you trusted have been careless with your dignity is painful. The person is not only dealing with a word but with a gap between the friendship they thought they had and the reality that is showing up.

Healing from this kind of experience begins with honesty about the impact. Instead of brushing off the label as “no big deal”, it helps to recognise how it has affected sleep, mood, energy, and behaviour. Naming the harm is not being dramatic. It is simply gathering accurate information about what has been happening. Once the effect is acknowledged, it becomes possible to challenge the idea that the label is an objective truth. Someone else’s behaviour, shaped by their own insecurities, humour style, or biases, does not automatically become a fact about another person’s worth.

Separating behaviour from identity can take time. It might involve consciously changing the way one talks about the experience. For example, saying “They chose to call me chopped, that reflects their mindset” rather than “I am chopped and that is all I will ever be”. This kind of language does not magically fix everything, but it nudges the brain away from seeing the insult as a permanent part of the self.

It is also important to examine the friendships themselves. Patterns matter more than isolated incidents. If the same people keep using words that drag someone down, if the jokes are one sided, or if respect appears only when it is convenient, those are signs that the culture of the group may be unhealthy. Everyone deserves to be around people who can laugh without making someone feel small. If attempts to set boundaries are ignored or mocked, that provides valuable information about whether these relationships truly support long term wellbeing.

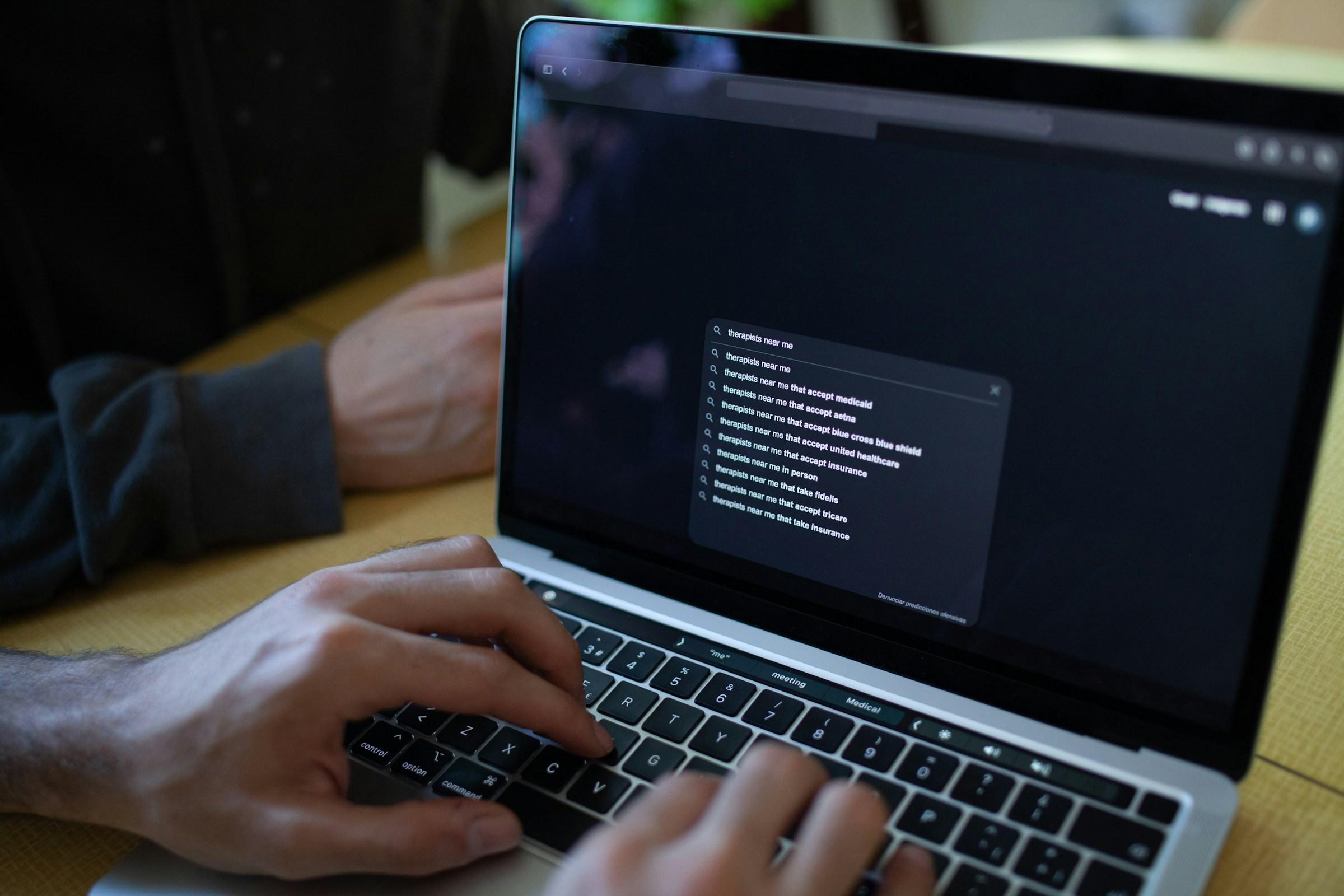

Sometimes the hurt has already sunk deep enough that self help alone is not enough. In those cases, reaching out for professional support can be crucial. A therapist, counsellor, or trusted mentor can help untangle the label from the person’s identity, rebuild self esteem, and develop healthier patterns of relating to others. There is no weakness in asking for help. In fact, it shows a strong desire to protect one’s own mental health rather than leaving it in the hands of people who have not handled it carefully.

In the end, the effects of being labelled chopped on mental health are about much more than a single word. They reflect how social verdicts can seep into self perception, how jokes can slowly erode self esteem, and how an environment that treats someone as disposable can train them to accept less than they deserve. The goal is not to create a life where no one ever says anything harsh. That is impossible. The goal is to build an inner and outer world where harsh words do not get to set the terms of a person’s entire story. Choosing friendships that do not need anyone to be small, curating online spaces that do not run on cruelty, and practising self talk that honours one’s inherent worth are all ways of doing that work. Over time, those choices can help loosen the grip of old labels and leave more room for confidence, stability, and genuine peace of mind.

.jpg&w=3840&q=75)

.jpg&w=3840&q=75)