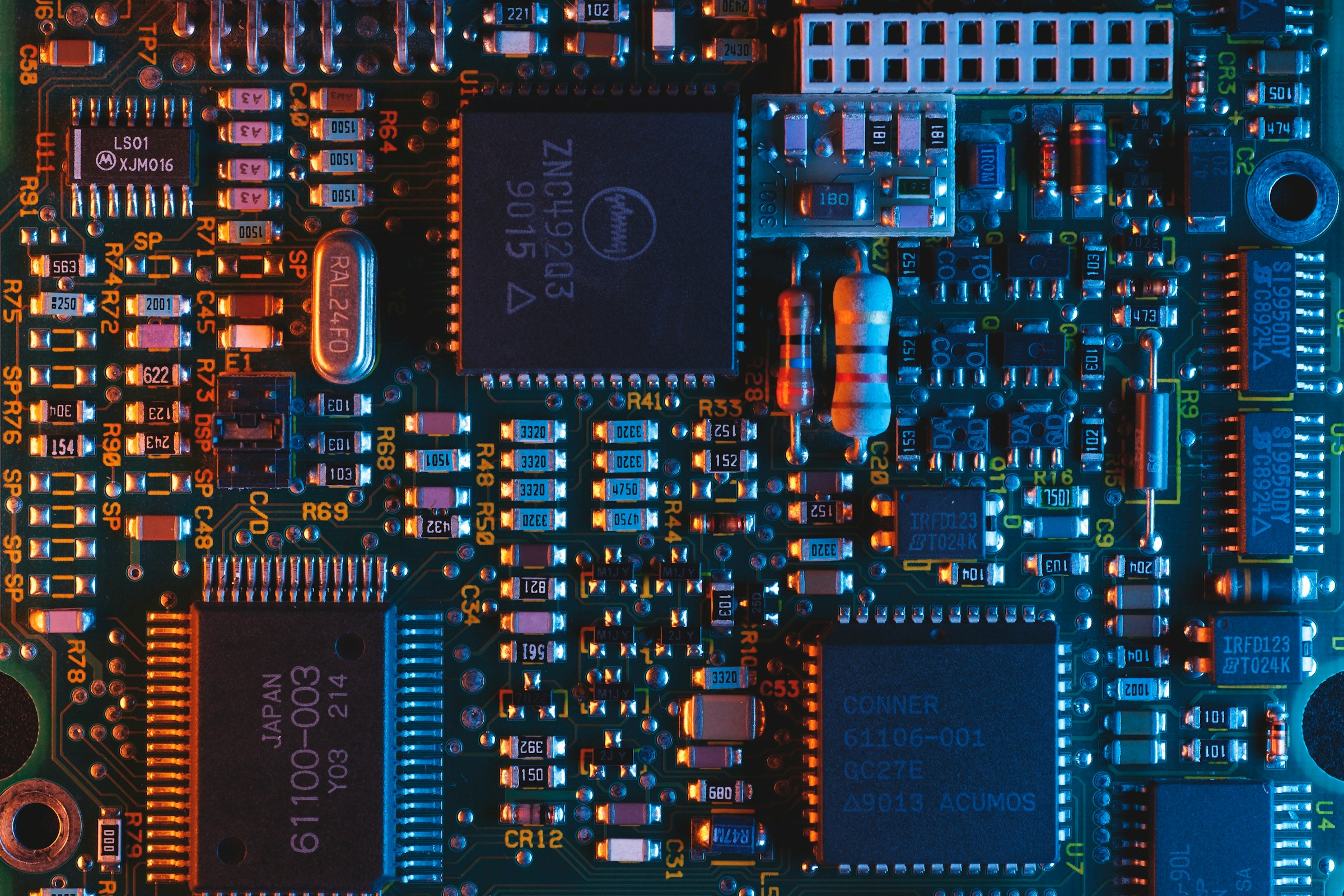

President Donald Trump has proposed a sweeping new trade measure that could impose a 100% tariff on semiconductor chips imported into the United States—unless the company producing them already manufactures in the US or has committed to doing so.

The measure, announced in an Oval Office briefing, targets non-domestic chip production. While not a formal policy yet, the proposal outlines a hard-line stance toward foreign semiconductor suppliers and appears aimed at deepening the onshoring momentum triggered by the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022.

This isn’t just tariff talk. It’s a structural signal: comply with US-based production, or face delayed fiscal penalties that could reshape investment logic globally.

Trump’s remarks suggest a deeper evolution of US industrial strategy. No longer satisfied with incentivizing onshore production through subsidies alone, the US is now entertaining retrospective punitive tariffs for non-compliant foreign manufacturers. If a company pledges to build a US facility but fails to follow through, the government “adds it up,” according to Trump—accumulating tariffs that must be paid at a later date.

This turns industrial policy into a dual-control mechanism: subsidy if you participate, tariff if you abstain or delay. That logic is more than protective—it’s disciplinary. And it represents a significant shift from globalized sourcing to compliance-driven production architecture.

The proposed tariff would largely spare chipmakers already investing in US fabrication. TSMC—Taiwan’s leading chip foundry—has US facilities under development, and major US firms like Nvidia, which rely on TSMC for production, are thus unlikely to be affected. Nvidia, for its part, has already signaled its intention to invest in domestic chip supply chains over the coming years.

Instead, the pain will be concentrated among Chinese chipmakers and non-committed foreign manufacturers, including firms whose chips enter the US embedded in consumer electronics or automotive components.

Huawei and SMIC, already under export controls, will face additional barriers if this tariff materializes. And the net could broaden to include any upstream players without a verifiable US manufacturing footprint or exemption under existing trade agreements.

For Southeast Asian or European firms that serve as lower-tier foundries, packaging providers, or assembly plants—this introduces tariff adjacency risk. Any chip with an ambiguous production lineage may invite compliance scrutiny, delaying shipments or forcing rerouting through approved partners.

Not all US partners will be hit equally. According to recent reports, the European Union, South Korea, and Japan have already negotiated de facto exemptions, with a 15% tariff ceiling covering a wide swath of exports including chips, pharmaceuticals, and automobiles.

These deals signal a strategic alignment effort by Washington: create a preferential corridor for like-minded allies while isolating supply chains deemed misaligned with US economic or security interests. It’s a carrot-and-stick arrangement embedded in tariff structure, and it reshapes the map for capital allocators, not just exporters.

Behind the policy noise is a deeper capital reallocation story. The US government has already seeded $52.7 billion in semiconductor subsidies to rebuild domestic capacity. That’s the carrot. Now comes the stick: a delayed tariff trap for those trying to operate without anchoring their capital in the US.

For private equity and sovereign funds with semiconductor exposure, this represents a new due diligence variable: production jurisdiction is now a financial risk, not just a supply chain detail.

Funds already invested in US-compliant chip supply chains—like Intel, Micron, and TSMC’s Arizona plant—stand to benefit from a reweighted capital environment. Meanwhile, investors exposed to fragmented or ambiguous production chains in Asia must assess whether tariff exposure could become a valuation drag, especially if the 100% rate becomes real policy.

Expect greater capital rotation toward US-aligned fabrication capacity—not because of price advantages, but because of regulatory immunity.

This proposed tariff framework does more than weaponize trade—it codifies industrial discipline into the global capital cycle. The message is clear: if you want access to the US market, your investment must match its national production interests.

This is not protectionism for its own sake. It’s about ensuring that national security imperatives—especially in AI, defense, and critical infrastructure—are met through domestic fabrication guarantees. By creating backward-looking penalties, the US now introduces time-bound compliance: you can delay your factory, but the tariff will find you later.

In that sense, it shifts the US-China chip war into a broader sovereignty game for manufacturing commitments. Countries and companies that align now stand to gain subsidy and market access. Those that wait or hedge will face fiscal drag and policy uncertainty.

The 100% semiconductor tariff proposal may never be fully enacted—but the threat structure is real. Whether or not the policy is implemented in full, it’s already doing its job: shifting how investors, governments, and multinational manufacturers think about supply chain location and regulatory exposure.

This is less about restricting imports—and more about controlling capital behavior through industrial conditionality. The tariff may be optional for now. But compliance won’t be.

.jpeg&w=3840&q=75)